30 Years Ago: Clint Eastwood Demystifies His Legend in ‘Unforgiven’

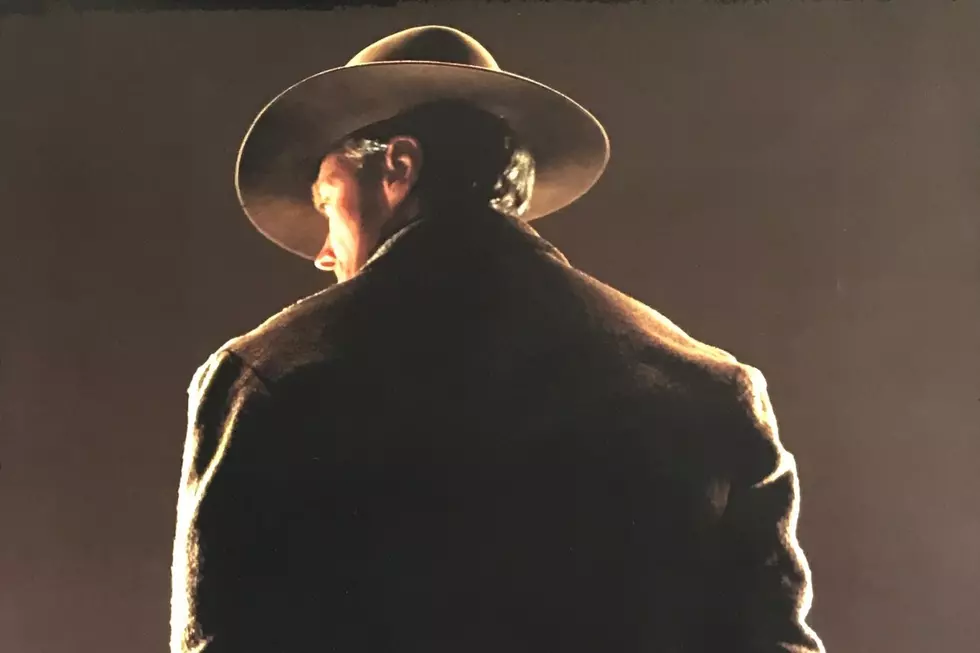

Westerns have always been about mythmaking. A uniquely American genre, the traditional Western elevated the lone gunslinger to a legendary figure, taming a lawless frontier with a lightning-fast draw. Nobody epitomized this more than Clint Eastwood, who, ironically, had to head to Italy to become the all-American hero in director Sergio Leone’s so-called “Spaghetti Westerns,” A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

Eastwood was the Man With No Name, a taciturn, iron-willed and seemingly indestructible antihero whose implacable drive for vengeance/justice left heaps of dusty, bloody bodies strewn all over the unforgiving landscape. It’s a myth the ambitious Eastwood leaned into as much as he began to deconstruct it once he embarked on his directorial career. In 1976’s The Outlaw Josey Wales, Eastwood’s gunslinger is as deadly as ever but more complicatedly human than Leone’s supercowboy. And Eastwood the director continued to muddy the hidebound Western archetypes (and his image) until 1985’s Pale Rider, where Eastwood’s unnamed, preacher-clad protagonist is represented more as an inhuman avenging spirit than a flesh-and-blood outlaw.

Eastwood’s post-Pale Rider career saw the director branching out with expectation-defying experiments like the Charlie Parker biopic Bird and 1990’s White Hunter, Black Heart, a thinly disguised depiction of the filming of The African Queen, with Eastwood putting on a polarizing imitation of director John Huston. It genuinely appeared as if Pale Rider was to be the former Western icon’s final foray into the genre he helped popularize.

So the announcement of 1992’s Unforgiven was greeted with something of a shrug. (It didn’t help that his previous film was a buddy cop flick alongside Charlie Sheen.) Sure, the now 62-year-old Eastwood would be portraying an aging gunfighter, lured out of retirement with the promise of one last payday. But the initial ads for the film played up the return of gruff, badass Old West Clint. A pivotal scene from the trailer saw Gene Hackman’s outraged sheriff cry, “You just shot an unarmed man!,” with a grizzled Eastwood quipping a glib-sounding, “Well, he should’ve armed himself.” The prospect of seeing another Eastwood Western was surely enough of a draw at that point, but nothing prepared audiences for what would become one of the best, most acclaimed, and emotionally and thematically richest Westerns ever.

David Webb Peoples’ script had been around since the '70s, and was optioned and dropped multiple times before Eastwood, seemingly destined to wait until he aged into the central part of William Munny, signed on as director and star. It’s the story of a formerly infamous outlaw whose transformation into an abstemiously loving husband and father is challenged by the news that a group of aggrieved prostitutes is offering a thousand-dollar bounty to anyone who’ll kill the two roughnecks who mutilated one of them. (Thankfully, Peoples’ original title, The Cut-Whore Killings, went away with a proposed 1980’s Francis Ford Coppola version, starring John Malkovich.)

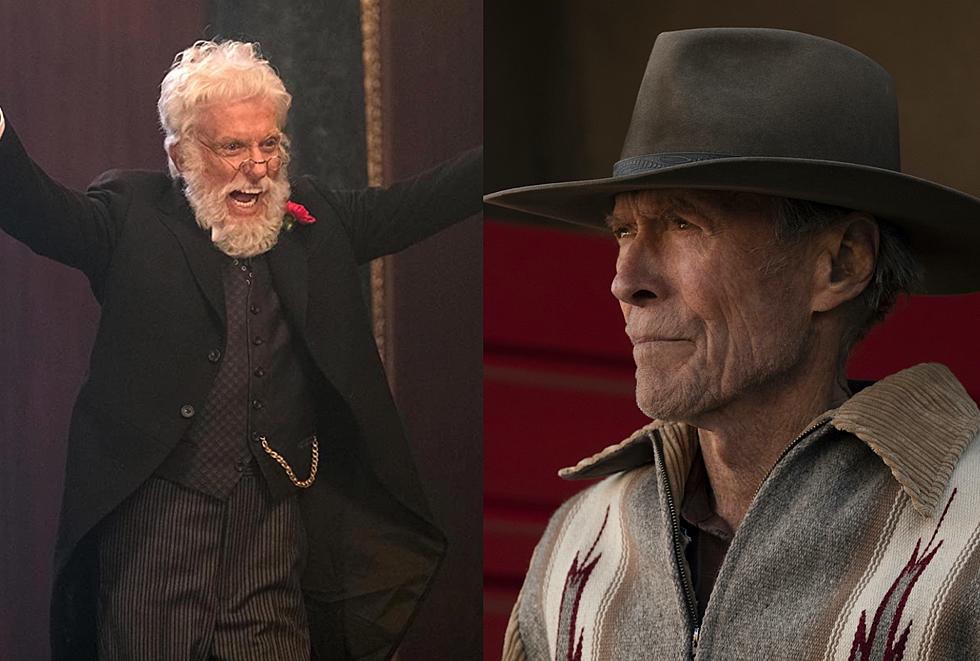

Eastwood’s Unforgiven takes place in a quickly developing Old West, where old gunslingers like Munny and former running partner Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman) have settled into creaky domesticity or seized upon lawman roles they once flouted, like Gene Hackman’s Little Bill Daggett, now the sheriff of the Wyoming town at the center of the prostitutes’ quest for vengeance. The myth of the Wild West is carried on here by callow punks like Jaimz Woolvett’s Scofield Kid, who seeks out the broke and widowed Munny for help in collecting the bounty, and active mythmakers like Saul Rubinek’s writer W.W. Beauchamp, who trails self-aggrandizing old gunmen like Richard Harris’ supercilious English Bob, delightedly taking down and embellishing old lies into printed legend.

The collision of all these forces sees Peoples and Eastwood feelingly and brutally stripping away the Western genre’s fanciest garments. Eastwood’s performance is oddly stiff at first, his William Munny speaking with a formality testifying to the strain of reining in his former wildness and recklessness. As he, Ned and the boastful Scofield Kid ride onto Hackman’s town of Big Whiskey, Wyo., the two old men begin to reminisce about — and rue — their former ways, with a fever-stricken Munny confessing that his drunken bloodlust has left him with nothing but regrets.

Watch the Trailer for 'Unforgiven'

The trio eventually fulfills their mission, but not before the secretly half-blind Kid breaks down after murdering one of the cowboys in an outhouse, confessing he’d never actually killed anyone and handing Will his revolver. Having been savagely beaten by Little Bill to discourage other fortune hunters, Will is forced to snipe the younger (and more sympathetic) cowboy when Ned can’t bring himself to pull the trigger and leaves for home.

It’s here that that climactic trailer scene comes into much more interesting focus, as Will, finding out that Little Bill has tortured the fleeing Ned to death for information and propped the old man’s body outside of the brothel-saloon as a further deterrent, takes his first drink of whiskey in ages, and sets out for revenge. In front of Little Bill and his gathered deputies, Will shoots the saloon owner and pimp Skinny and, to Bill’s objection, replies with the full line, “Well, he should have armed himself, if he’s gonna decorate his saloon with my friend.” Gunning down Little Bill to complete his revenge, Munny somberly replies to Bill claiming, “I don’t deserve this, to die like this,” with the pronouncement, “Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it.”

Those are killer Western tough guy lines, and Eastwood isn’t unaware of their power to perpetuate the myths he’s been deconstructing. It’s the fact of W.W. Beauchamp’s worshipful appraisal of Munny’s improbable handiwork that Unforgiven plays its last card, however. Having ditched the humiliated English Bob for Little Bill’s brand of revisionist gunslinger history, he now gravitates toward Munny, his brain whirring as he commences rewriting the ugly events he’s just witnessed into yet another thrilling tale of larger-than-life adventure. Beauchamp (patterned on real-life Old West chronicler and exaggerator Ned Buntline) prattles on until the unamused Munny shoos him away, leaving little doubt as to this is Eastwood’s opinion of those seeking to glorify Unforgiven’s grubby violence and dead-end bravado.

Unforgiven - released on Aug. 7, 1992 - cleaned up at the Oscars that year, with Eastwood winning the first of his two Best Director awards, Hackman winning for Best Supporting Actor and the film taking home Best Picture. Everyone in the movie (including Frances Fisher as Strawberry Alice, the most vengeance-minded of the prostitutes) is pitch-perfect in their roles (Freeman and Harris could easily have joined Hackman on awards night), and Eastwood cannily frames his Alberta landscapes in a golden, elegiac glow increasingly at odds with the film’s darkening themes. Peoples’ script is a marvelous construction, its central plot a vehicle for Eastwood’s massaging and festooned with witty embellishments and tight little exchanges for Eastwood’s cast to shine.

In the end, a crawl anticlimactically assures us that William Munny retired to a life of relative prosperity in San Francisco with his children, his lifetime of once-feared deeds fading away along with the abandoned farm he once shared with his wife. Eastwood himself was propelled into the ranks of prestige directors, turning out largely respected big-budget films even as his always curmudgeonly politics curdled into prosaic jingoism at times. Unforgiven, though, remains a singular achievement. Westerns made Clint Eastwood. And then, in his final Western to date, Clint Eastwood turned the camera on himself and his legacy to produce one of the finest Westerns ever made.